2023 Kentucky KIDS COUNT Data Dashboard

Please visit this page from a desktop browser to view our interactive data dashboard

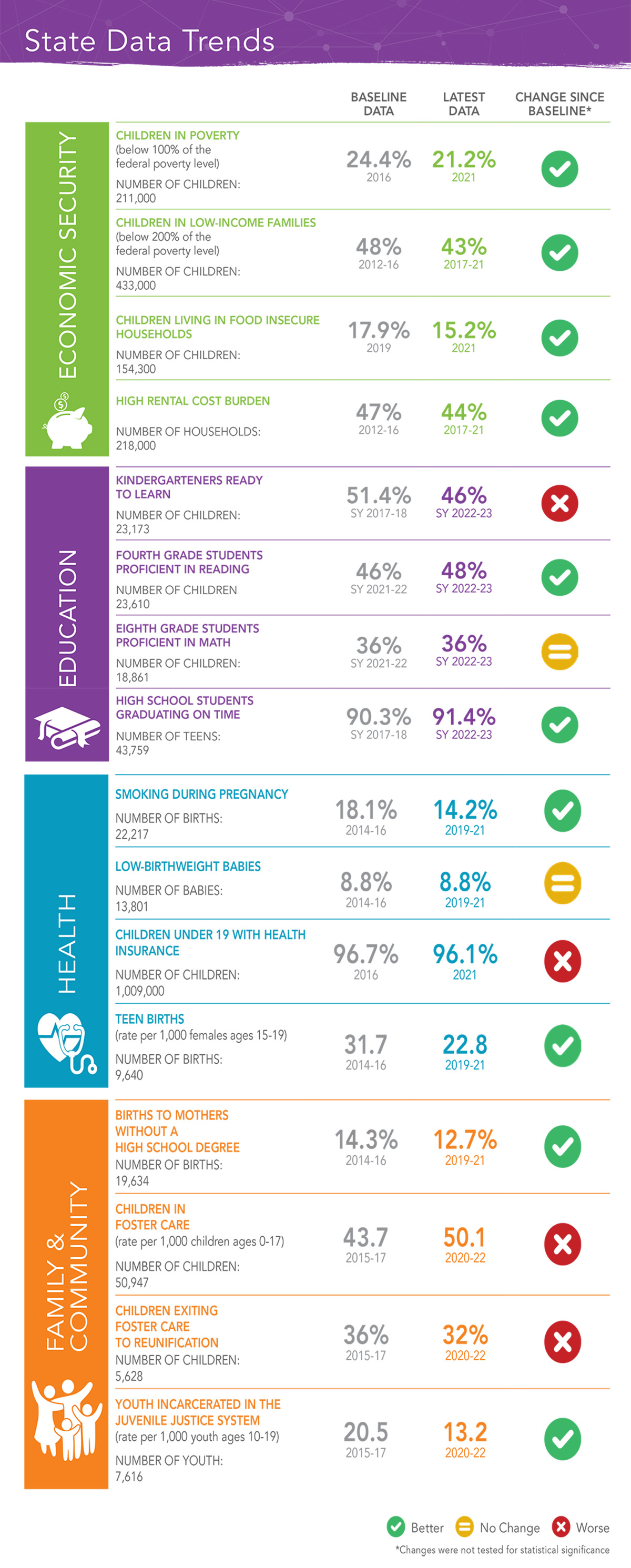

ECONOMIC SECURITY

Baseline Data

Latest Data

Change Since Baseline*

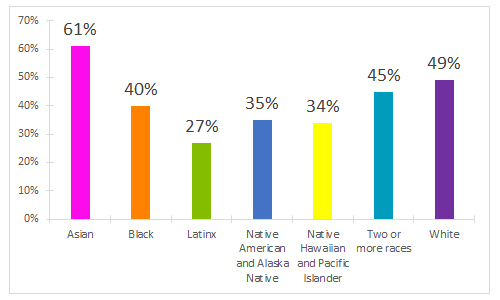

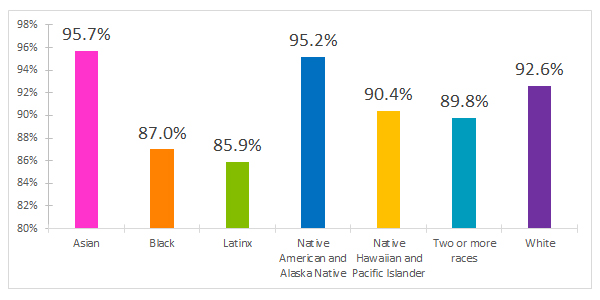

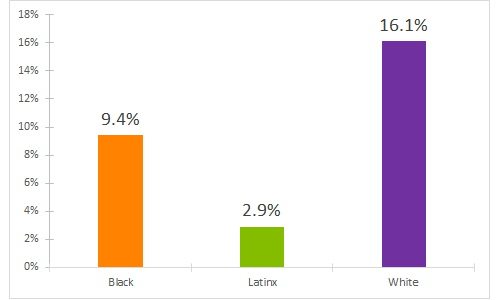

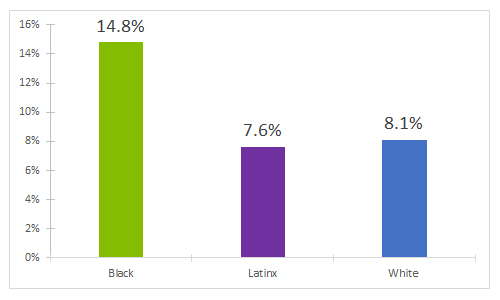

Data by Race/Ethnicity

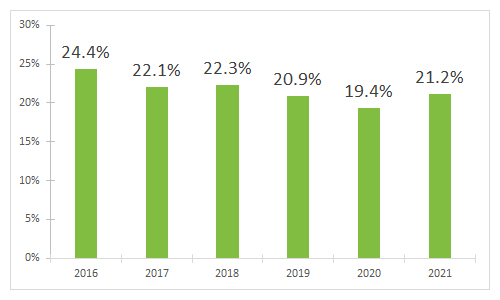

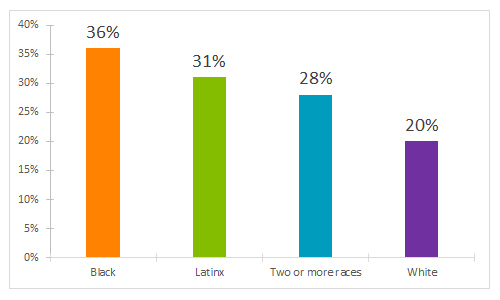

CHILDREN IN POVERTY

(below 100% of the federal poverty level)

NUMBER OF CHILDREN: 211,000

24.4%

2016

21.2%

2021

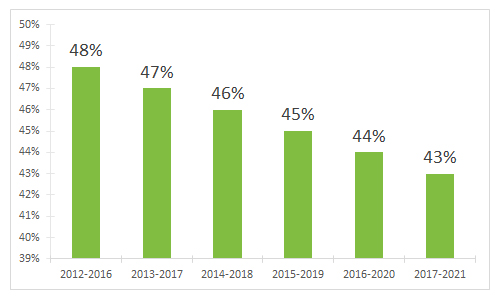

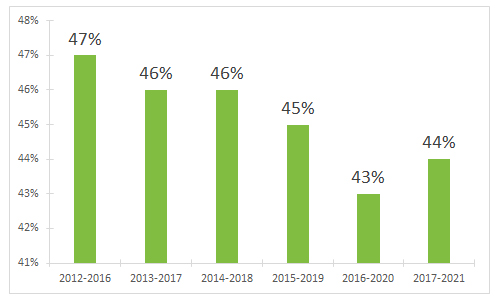

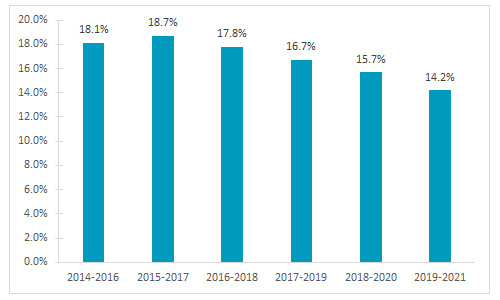

CHILDREN IN LOW-INCOME FAMILIES

(below 200% of the federal poverty level)

NUMBER OF CHILDREN: 433,000

48%

2012-16

43%

2017-21

EDUCATION

Baseline Data

Latest Data

Change Since Baseline*

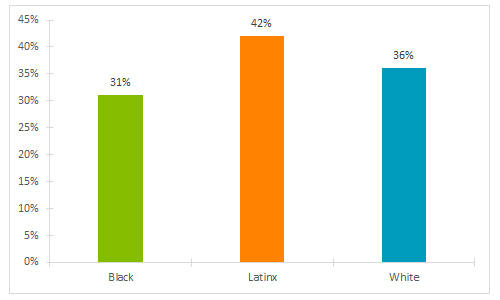

Data by Race/Ethnicity

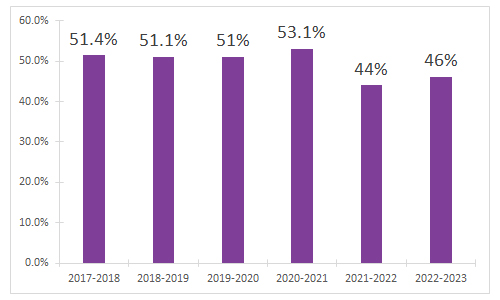

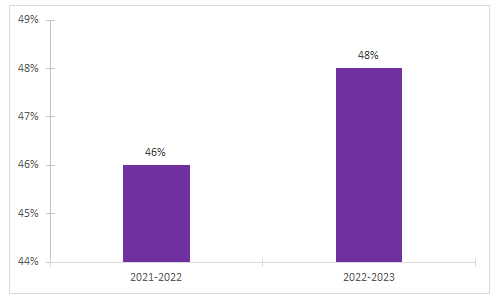

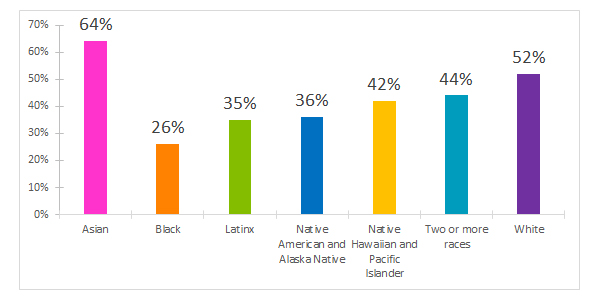

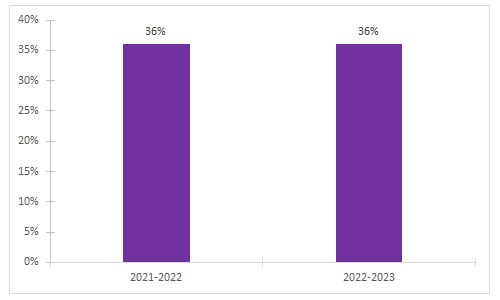

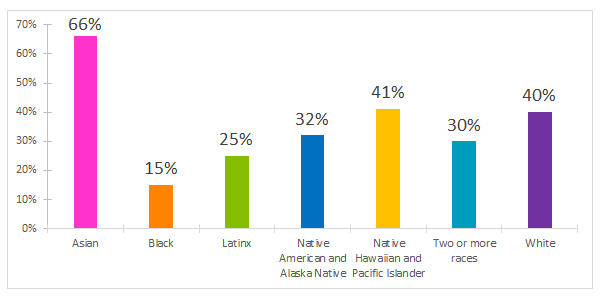

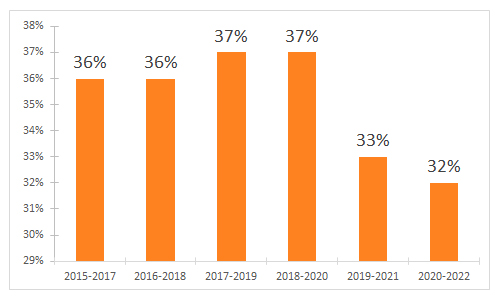

FOURTH GRADE STUDENTS PROFICIENT IN READING

NUMBER OF CHILDREN: 23,610

46%

SY 2021-22

48%

SY 2022-23

HEALTH

Baseline Data

Latest Data

Change Since Baseline*

Data by Race/Ethnicity

FAMILY & COMMUNITY

Baseline Data

Latest Data

Change Since Baseline*

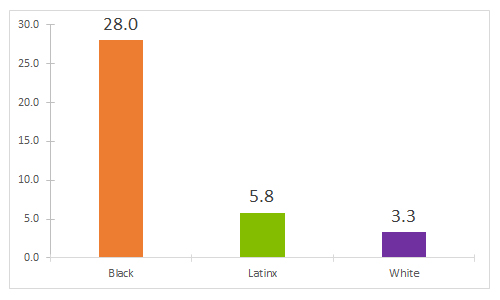

Data by Race/Ethnicity

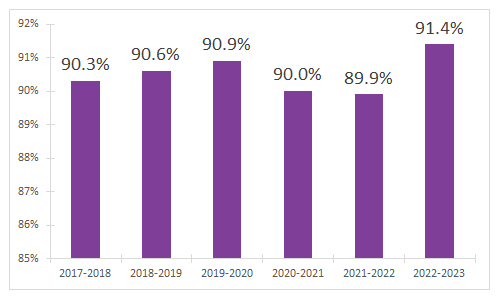

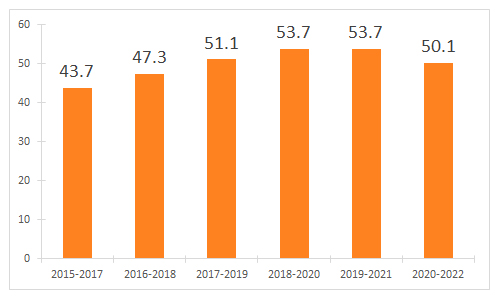

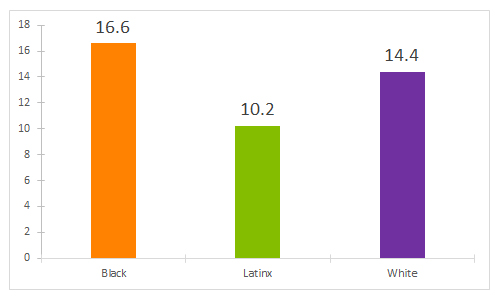

CHILDREN IN FOSTER CARE

(rate per 1,000 children ages 0-17)

NUMBER OF CHILDREN: 50,947

43.7

2015-17

50.1

2020-22

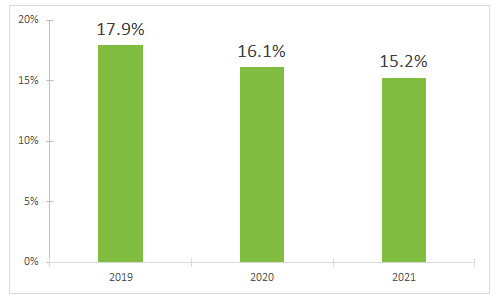

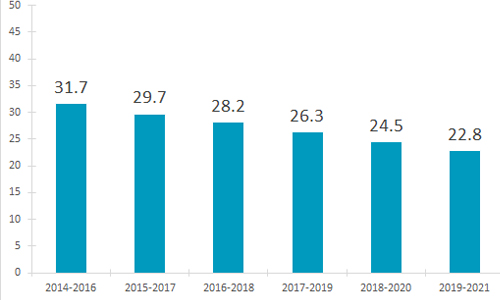

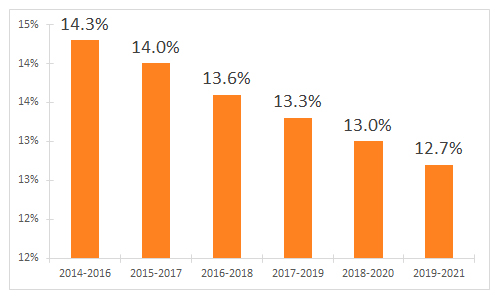

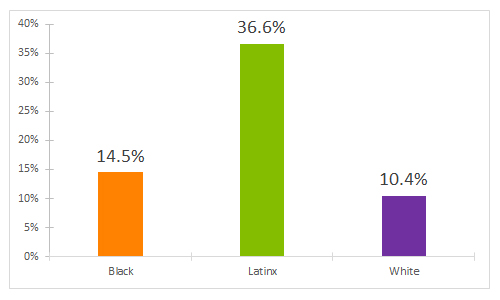

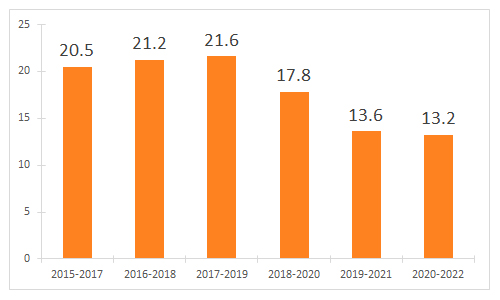

YOUTH INCARCERATED IN THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM

(rate per 1,000 youth ages 10-19)

NUMBER OF YOUTH: 7,616

20.5

2015-17

13.2

2020-22

Data Dashboard updated November 2023